Culture & Customs

Belling Slaves:

“’In the cities,’ I said, ‘only Pleasure Slaves are so belled, and then customarily for the dance.’

“‘Her master,’ said Kamchak, ‘does not trust her.’

“In his simple statement I then understood the meaning of her condition. She would be allowed no garments, that she might not be able to conceal a weapon; the bells would mark each of her movements.”—Nomads, 29

“’Tomorrow, Little Aphris,’ said he,‘I will give you something to wear.’

"She looked at him gratefully.

"’Bells and a collar,’ said he.

"Tears appeared in her eyes.

"’Can I trust you?’ he said.

"’No,’ she said.

"’Bells and collar,’ said he. ‘But I shall wind them about with strings of diamonds—that those who see will know that your master can well afford the goods you will do without.’“—Nomads, 143

Bosk, Uses of:

“Not only does the flesh of the bosk and the milk of its cows furnish the Wagon Peoples with food and drink, but its hides cover the domelike wagons in which they dwell; its tanned and sewn skins cover their bodies; the leather of its hump is used for their shield; its sinews forms their thread; its bones and horns are split and tooled into implements of a hundred sorts, from awls, punches, and spoons to drinking flagons and weapon tips; its hooves are used for glues; its oils are used to grease their bodies against the cold. Even the dung of the bosk finds uses on the treeless prairies, being dried and used for fuel.”—Nomads, 5

Calendars, Men’s and Women’s:

“A consequence of the chronological conventions of the Wagon Peoples, of course, is that their years tend to vary in length, but this fact, which might bother us, does not bother them, any more than the fact that some men and some animals live longer than others; the women of the Wagon Peoples, incidentally, keep a calendar based on the phases of Gor's largest moon, but this is a calendar of fifteen moons, named for the fifteen varieties of bosk, and functions independently of the tallying of years by snows; for example, the Moon of the Brown Bosk may at one time occur in the winter, at another time, years later, in the summer; this calendar is kept by a set of colored pegs set in the sides of some wagons, on one of which, depending on the moon, a round, wooden plate bearing the image of a bosk is fixed. The years, incidentally, are not numbered by the Wagon Peoples, but given names, toward their end, based on something or other which has occurred to distinguish the year.”—Nomads, 12

Courage, Courage Scar; Importance of:

"..I recalled what I had heard whispered of once before, in a tavern in Ar, the terrible Scar Codes of the Wagon Peoples, for each of the hideous marks on the faces of these men had meaning, a significance that could be read by the Paravaci, the Kassars, the Kataii, the Tuchuks as clearly as you or I might read a sign in a window or a sentence in a book. At that time I could only read the top scar, the red, bright, fierce, cordlike scar that was the Courage Scar. It is always the highest scar on the face. Indeed, without that scar, no other scar can be granted. The Wagon Peoples value courage above all else.”—Nomads, 16

“I had determined, of course, to my satisfaction, having spoken with him once, that the boy, or young man, was indeed Gorean; his people and their people before them and as far back as anyone knew had been, as it is said, of the Wagons. The problem of the young man, and perhaps the reason that he had not yet won even the Courage Scar of the Tuchuks, was that he had fallen into the hands of Turian raiders in his youth and had spent several years in the city; in his adolescence he had, at great risk to himself, escaped from the city and made his way with great hardships across the plains to rejoin his people; they, of course, to his great disappointment, had not accepted him, regarding him as more Turian than Tuchuk. His parents and people had been slain in the Turian raid in which he had been captured, so he had no kin. There had been, fortunately for him, a Year Keeper who had recalled the family. Thus he had not been slain but had been allowed to remain with the Tuchuks. He did not have his own wagon or his own bosk. He did not even own a kaiila. He had armed himself with castoff weapons, with which he practiced in solitude. None of those, however, who led raids on enemy caravans or sorties against the city and its outlying fields, or retaliated upon their neighbors in the delicate matters of bosk stealing, would accept him in their parties. He had, to their satisfaction, demonstrated his prowess with weapons, but they would laugh at him. ‘You do not even own a kaiila,’ they would say. ‘You do not even wear the Courage Scar.’ I supposed that the young man would never be likely to wear the scar, without which, among the stern, cruel Tuchuks, he would be the continuous object of scorn, ridicule and contempt. Indeed, I knew that some among the wagons, the girl Hereena, for example, who seemed to bear him a great dislike, had insisted that he, though free, be forced to wear the Kes or the dress of a woman. Such would have been a great joke among the Tuchuks.”—Nomads, 68

“…Indeed, without the Courage Scar one could not even think of proposing oneself for the competition [of the Games of Love War]. It might be mentioned, incidentally, that without the Courage Scar one may not, among the Tuchuks, pay court to a free woman, own a wagon, or own more than five bosk and three kaiila. The Courage Scar thus has its social and economic, as well as its martial, import.”—Nomads, 113

“’I am serious,’ he averred. ‘The night that you and I departed for Turia, Kamchak ordered a wagon prepared for each of us—to reward us.’

“…’But to reward us for what?’ I asked.

“’For courage,’ he said.

“’Just that?’ I asked.

“’But for what else?’ asked Harold.

“’For success.’ I said. ‘You were successful. You did what you set out to do. I did not. I failed. I did not obtain the golden sphere.’

“…’But you were successful,' insisted Harold.

“’How is that?’ I asked.

“’To a Tuchuk,’ said Harold, ‘success is courage—that is the important thing—courage itself—even if all else fails—that is success…That in entering Turia—and escaping as we did—even bringing tarns to the camp—we—the two of us—won the Courage Scar.”—Nomads, 273

‘“When I have the time,’ said Harold, “I will call one from the clan of Scarers and have the scar affixed. It will make me look even more handsome.

“I smiled.

“’Perhaps you would like me to call him for you as well?’ inquired Harold.

“’No,’ I said.

“’It might take attention away from your [bright red] hair,’ Harold mentioned.

“’No, thank you,’ I said.

“’All right,’ said Harold, ‘it is well known you are Koroban, and not Tuchuk.’ But then he added, soberly, ‘But you wear the Courage Scar for what you did—not all men who wear the Courage Scar do so visibly.’”—Nomads, 274

City Dwellers, Views on:

“Then he said, ‘Though you are a dweller of the cities—a vermin of the walls—I think you are not unworthy—and thus I pray the lance will fall to me.’”—Nomads, 19

Collar Inscriptions:

“She could speak Gorean, but she could not read it. For that matter many Tuchuks could not, and the engraving on the collars of their slaves was often no more than a sign which was known to be theirs. Even those who could read, or pretended to be able to, would affix their sign on the collar as well as their name, so that others who could not read could know to whom the slave belonged. Kamchak’s sign was the four bosk horns and two quivas.

“The engraving on the Turian collar consisted of the sign of the four bosk horns and the sign of the city of Ko-ro-bo, which I took it, Kamchak had used for my sign. There was also an inscription on the collar, a simple one: I am Tarl Cabot’s girl.”—Nomads, 279

Diversity of the Tuchuk Culture:

“…We were jostled by armed warriors, scarred and fierce; by boys with unscarred faces, carrying the pointed sticks often used for goading the wagon bosk; by leather-clad women hurrying from the cooking pots; by wild, half-clothed children; even by enslaved, clad-Kajir beauties of Turia…

“We suddenly emerged in the center of what seemed to be a wide, grassy street among the wagons, a wide lane, open and level, an avenue in that city of Harigga, or Bosk Wagons.

“The street was lined by throngs of Tuchuks and slaves. Among them, too, were soothsayers and haruspexes, and singers and musicians, and, here and there, small peddlers and merchants, of various cities, for such are occasionally permitted by the Tuchuks, who crave their wares, to approach the wagons. Each of these, I was later to learn, wore on his forearm a tiny brand, in the form of spreading bosk horns, which guaranteed his passage, at certain seasons, across the plains of the Wagon Peoples. The difficulty, of course, is in first obtaining the brand. If, in the case if a singer, his song is rejected, or in the case of a merchant, his merchandise is rejected, he is slain out of hand."-Nomads, 34

Dais of the Ubar:

“But I did not enter the wagon, for Kutaituchik held his court outside the wagon, in the open air, on the flat-topped grassy hill. A large dais had been built, vast and spreading, but standing no more than a foot from the earth. This dais was covered with dozens of thick rugs, sometimes four and five deep.

“There were many Tuchuks, and some others, crowded about the dais, and, standing upon it, about Kutaituchik, there were several men who, from their position on the dais and their trappings, I judged to be of great importance.

“About Kutaituchik there were piled various goods, mostly vessels of precious metals and strings and piles of jewels; there was silk from Tyros; silver from Thentis and Tharna; tapestries from the mills of Ar; wines from Cos; dates from the city of Tor. There were also, among other goods, two girls, blonde and blue-eyed, unclothed, chained; they had perhaps been a gift to Kutaituchik; or had been the daughters of enemies; they might have been from any city; both were beautiful…

“At the edge of the dais Kamchak and I had stopped, where our sandals were removed and our feet washed by Turian slaves, men in the Kes, who might once have been officers of the city.

“We mounted the dais and approached the seemingly somnolent figure upon it.

“Although the dais was resplendent, and the rugs upon it even more resplendent, I saw that beneath Kutaituchik, over these rugs, had been spread the simple, worn, tattered robe of gray boskhide. It was upon this simple robe that he sat. It was undoubtedly that of which Kamchak had spoken, the robe upon which sits the Ubar of the Tuchuks, that simple robe which is his throne…

“We simply sat near him, cross-legged. I was conscious that only we three on the dais were sitting. I was pleased that there were not prostrations or grovelings involved in approaching the august presence of the exalted Kutaituchik.”—Nomads, 41-43

Eating Customs: Tuchuks eat their bosk meat in a rather odd and distinctive way.

“He was eating the piece of bosk meat in the Tuchuk fashion, holding the meat in his left hand and between his teeth, and cutting pieces from it with a quiva scarcely a quarter inch from his lips, then chewing the severed bite and then again holding the meat in his hand and teeth and cutting again…finishing his meat and wiping his mouth in Tuchuk fashion on the back of his right sleeve…carefully wiping the quiva on the back of his left sleeve.“—Nomads, 186-7

First Wagon, Of The:

“’What does it mean to be of the First Wagon?’ I asked.

“Kamchak laughed. ‘You know little of the Wagon Peoples’ he said.

“’That is true,’ I admitted.

“’To be of the First Wagon, said Kamchak, ‘is to be of the household of Kutaituchik…There are a hundred wagons in the personal household of Kutaituchik…To be of any of these wagons is to be of the First Wagon.’’

“I see,’ I said. ‘And the girl—she on the kaiila—is perhaps the daughter of Kutaituchik, Ubar of the Tuchuks?’

“’No,’ said Kamchak, ‘she is unrelated to him, as are most in the First Wagon.’”—Nomads, 32-3

Funeral Rites:

"I had found Kamchak, as I had been told I would, at the wagon of Kutaituchik, which, drawn up on its hill near the standard of the four bosk horns, had been heaped with what wood was at hand and filled with dry grass. The whole was then drenched in fragrant oils, and... Kamchak, by his own hand, hurled the torch into the wagon. Somewhere in the wagon, fixed in a sitting position, weapons at hand, was Kutaituchik, who had been Kamchak's friend, and who had been called Ubar of the Tuchuks...

"At last when the wagon had burned and the wind moved about the blackened beams and scattered ashes across the green prairie, Kamchak raised his right hand. 'Let the standard be moved,' he cried."--Nomads, 232-3

Gamboling with the Lance:

“As I watched, the Tuchuk took his long, slender lance and thrust it into the ground, point upward. Then, slowly, the four riders began to walk their mounts about the lance, watching it, right hands free to seize it should it begin to fall…

“In their way I knew they were honoring me, that they had respected my stand in the matter of the charging lances, that now they were gamboling to see who would win me, to whose weapons my blood must flow, beneath the paws of whose kaiila I must fall bloodied to the earth.”—Nomads, 21

Greetings: Those of the Wagons have a unique and rather ironic form of greeting representative of both the humor and the lifestyle of the four Peoples.

“He grinned a Tuchuk grin. ‘How are the bosk?’ he asked.

“‘As well as may be expected,’ said Kamchak.

“‘Are the quivas sharp?’

“‘One tries to keep them so,’ said Kamchak.

“‘It is important to keep the axles of the wagons greased,’ observed Kutaituchik.

“‘Yes,’ said Kamchak, ‘I believe so.’

“Kutaituchik suddenly reached out and he and Kamchak, laughing, clasped hands.”—Nomads, 44

Grey Robe, The:

“’His wagon,’ smiled Kamchak, ‘is the First Wagon—and it is Kutaituchik who sits upon the grey robe.’

“’The gray robe?’ I asked.

“’That robe,’ said Kamchak, ‘which is the throne of the Ubars of the Tuchuks.’”—Nomads, 32

“Although the dais was resplendent, and the rugs upon it even more resplendent, I saw that beneath Kutaituchik, over these rugs, had been spread the simple, worn, tattered robe of gray boskhide. It was upon this simple robe that he sat. It was undoubtedly that of which Kamchak had spoken, the robe upon which sits the Ubar of the Tuchuks, that simple robe which is his throne…”—Nomads, 42-3

Kaiila Riding, Being Taught:

“Not a rider was thrown or seemed for an instant off balance. The children of the Wagon Peoples are taught the saddle of the kaiila before they can walk.”—Nomads, 17

Kaiila Riding, Transporting a Captive:

“Now I could see down the wide, grassy lane, loping towards us, two kaiila and riders. A lance was fastened between them, fixed to the stirrups of their saddles. The lance cleared the ground, given the height of the kaiila, by about five feet. Between the two animals, stumbling desperately, her throat bound by leather thongs to the lance behind her neck, ran a girl, her wrists tied behind her back.”—Nomads, 35

"The saddle of the kaiila, like the tarn saddle, is made in such a way as to accomodate, bound across it, a female captive, rings being fixed on both sides [of the pommel] through which binding fiber or thong may be passed." -- Nomads, 70

Merchant Brands:

“Among them, too, were soothsayers and haruspexes, and singers and musicians, and, here and there, small peddlers and merchants, of various cities, for such are occasionally permitted by the Tuchuks, who crave their wares, to approach the wagons. Each of these, I was later to learn, wore on his forearm a tiny brand, in the form of spreading bosk horns, which guaranteed his passage, at certain seasons, across the plains of the Wagon Peoples. The difficulty, of course, is in first obtaining the brand. If, in the case if a singer, his song is rejected, or in the case of a merchant, his merchandise is rejected, he is slain out of hand."-Nomads, 34

Nose Rings:

“These women were unscarred, but like the bosk themselves, each wore a nose ring. That of the animals is heavy and gold, that of the women also of gold but tiny and fine, not unlike the wedding rings of my old world.”—Nomads, 27

Naming:

“It was said a youth of the Wagon Peoples was taught the bow, the quiva, and the lance before their parents would consent to give them a name, for names are precious among the the Wagon Peoples, as among Goreans in general, and they are not to be wasted on one who is likely to die, one who cannot handle the weapons of the hunt and war. Until the youth has mastered the bow, the quiva, and the lance he is simply known as the first, or the second, and so on, son of such and such a father."—Nomads, 11

Omen Year:

“The Wagon Peoples war among themselves, but once in every two hands of years, there is a time of gathering of the peoples, and this, I had learned, was that time. In the thinking of the Wagon Peoples it is called the Omen Year, though the Omen Year is actually a season, rather than a year, which occupies a part of two of their regular years, for the Wagon Peoples calculate the year from the Season of Snows to the Season of Snows;

Turians, incidentally, figure the year from summer solstice to summer solstice; Goreans generally, on the other hand, figure the year from vernal equinox to vernal equinox, their new year beginning, like nature's, with the spring; the Omen Year, or season, lasts several months, and consists of three phases, called the Passing of Turia, which takes place in the fall; the Wintering, which takes place north of Turia and commonly south of the Cartius, the equator of course lying to the north in this hemisphere; and the Return to Turia, in the spring, or, as the Wagon Peoples say, in the Season of Little Grass. It is near Turia, in the spring, that the Omen Year is completed, when the omens are taken usually over several days by hundreds of haruspexes, mostly readers of bosk blood and verr livers, to determine if they are favorable for a choosing of a Ubar San, a One Ubar, a Ubar who would be High Ubar, a Ubar of all the Wagons, a Ubar of all the Peoples, one who could lead them as one people.”—Nomads, 11-12

“The herds would circle Turia, for this was the portion of the Omen Year that was called the Passing of Turia, in which the Wagon Peoples gather and begin to move toward their winter pastures; the second portion of the Omen Year is the Wintering, which takes place far north of Turia, the equator being approached in this hemisphere, of course, from the south; the third and final portion of the Omen Year is the Return to Turia, which takes place in the spring, or as the Wagon Peoples have it, in the Season of Little Grass. It is in the spring that the omens are taken, regarding the possible election of the Ubar San, the One Ubar, who would be Ubar of all the Wagons, of all the Peoples.”—Nomads, 55

“’After the games of Love War,’ said Kamchak, ‘The omens will be taken.’”

“….Even in the time I had been with the wagons I had gathered that it was only the implicit truce of the Omen Year which kept these four fierce, warring people from lunging at one another’s throats, or more exactly put, at one another’s bosk…I originally regarded the Omen Year as a rather pointless institution, but I came to later see that there is much to be said for it: it brings the Wagon Peoples together from time to time, and in this time, aside from the simple values of being together, there is much bosk trading and some exchange of women, free as well as slave; the bosk trading generally refreshes the herds and I expect much the same thing, from the point of view of biology, can be said of the exchange of the women; more importantly, perhaps, for one can always steal women and bosk, the Omen Year provides an institutionalized possibility for the uniting of the Wagon Peoples in a time of crisis, should they be divided and threatened. I think that those of the Wagons who instituted the Omen Year, more than a thousand years ago, were wise men.”—Nomads, 56

“…the Omen Year occurs only every tenth year.”—Nomads, 115

Oral Literature:

"The Wagon Peoples do not trust important matters, such as year names, to paper or parchment, subject to theft, insect and rodent damage, deterioration, etc. Most of those of the Wagon Peoples have excellent memories, trained from birth. Few can read, though some can, perhaps having acquired the skill far from the wagons, perhaps from merchants or tradesmen. The Wagon Peoples, as might be expected, have a large and complex oral literature. This is kept by and occasionally, in parts, recited by the Camp Singers.”—Nomads, 12

“Once, long ago, Ko-ro-ba and Ar had turned the invasion of the united Wagon Peoples from the north, and the memories of these things, stinging still in the honest songs of the camp skalds, would rankle in the craws of such fierce, proud people.”—Nomads,18

Ownership Ritual:

“The warrior leapt from the dias and, in a few moments, returned with a handful of roasted bosk meat.

“Kutaituchik gestured for the girl, trembling, to be brought forward, and the two warriors brought her to him, placing her directly before him.

“He took the meat in his hand and gave it to Kamchak, who bit into it, a bit of juice running at the side of his mouth; Kamchak then held the meat to the girl…

“Elizabeth Cardwell took the meat in her two hands, confined before her in slave bracelets and the chain of the Sirik, and, bending her head, her hair falling forward, ate it.

“She, a slave, had accepted meat from the hand of Kamchak of the Tuchuks.

“She belonged to him now.”—Nomads, 54

Pricing:

“He pointed to the necklace…

“’It will buy ten bosks,’ said he, ‘twenty wagons covered with golden cloth, a hundred she-slaves from Turia.’”—Nomads, 20

Thus, from this quote, we can gather that a single bosk is worth twice as much as a single richly furnished wagon and is equal to the purchase price of five Turian slaves (since there is a wagon:slave ratio of 1:5 in the quote above).

One may also infer that five slaves or one wagon are of about the same cost. We know as well that one who does not wear the Courage Scar may own no more than five bosk and three kaiila. A kaiila, then, must be even more expensive than a bosk. Though we are not told, perhaps not every Tuchuk man is an Outrider just as in the Medieval Ages, only men of some wealth were able to afford the horse, armor, and weapons that were the accoutrements of knighthood.

Religion:

“Then, furiously, the scars wild in his face, he sprang up in the stirrups and lifted both hands to the sky. ‘Spirit of the Sky,’ he cried, ‘let the lance fall to me—to me!’’—Nomads, 21

“The Tuchuk removed his helmet and threw It to the grass. He jerked open the jacket he wore and the leather jerkin beneath, revealing his chest.

“He looked about him, at the distant bosk herds, lifted his head to see the sky once more…

“The Tuchuk now looked at me swiftly. He did not expect nor would he receive aid from his fellows.”—Nomads, 25-6

“I heard a haruspex singing between the wagons; for a piece of meat he would read the wind and the grass; for a cup of wine the stars and the flight of birds; for a fat-bellied dinner the liver of a sleen or slave.

“The Wagon Peoples are fascinated with the future and its signs and though, to hear them speak, they put no store in such matters, yet they do in practice give them great consideration. I was told by Kamchak that once an army of a thousand wagons turned aside because a swarm of rennels, poisonous, crablike desert insects, did not defend its broken nest, crushed beneath the wheel of the lead wagon. Another time, over a hundred years ago, a wagon Ubar lost his spur from his right boot and turned for this reason back from the mighty gates of Ar itself.”—Nomads, 27-8

“The Tuchuks and other Wagon Peoples reverence Priest-Kings, but unlike the Goreans in the cities, with their castes of Initiates, they do not extend to them the dignities of worship. I suppose the Tuchuks worship nothing, in the common sense of that word, but it is true they hold many things holy, among them the bosk and the skills of arms, but chief among the things before which the proud Tuchuk stands ready to remove his helmet is the sky, the simple, vast, beautiful sky, from which falls the rain that, in his myths, formed the earth, and the bosks, and the Tuchuks. It is to the sky that the Tuchuks pray when they pray, demanding victory and luck for themselves, defeat and misery for their enemies. The Tuchuk, incidentally, like others of the Wagon Peoples, prays only when mounted, only when in the saddle and with weapons at hand; he prays to the sky not as a slave to a Master, nor a servant to a god, but as a warrior to a Ubar; the women of the Wagon Peoples, it might be mentioned, are not permitted to pray; many of them, however, do patronize the haruspexes, who, besides foretelling the future with a greater or lesser degree of accuracy for generally reasonable fees, provide an incredible assemblage of amulets, talismans, trinkets, philters, potions, spell papers, wonder-working sleen teeth, marvelous powdered kailiauk horns, and colored, magic strings that, depending on the purpose, may be knotted in various ways and worn about the neck.”—Nomads, 28

“Kamchak smiled. ‘We are pleased to be of service to Priest-Kings,’ he said, ‘but remember that we reverence only the sky.’

“’And courage,’ added Harold, ‘and such things.’

“Kamchak and I laughed.

“’I think it is because—at least in part,’ I said, ‘that you reverence the sky—and courage—and such things—that the egg was brought to you.”—Nomads, 327

Scars, Scarring:

“On the face of each there were, almost like corded chevrons, brightly colored scars. The vivid coloring and intensity of these scars, their prominence, reminded me of the hideous markings on the faces of mandrills; but these disfigurements, as I soon recognized, were cultural, not congenital, and bespoke not the natural innocence of the work of genes but the glories and status, the arrogance and prides, of their bearers. The scars had been worked into the faces, with needles and knives and pigments and the dung of bosks over a period of days and nights. Men had died in the fixing of such scars. Most of the scars were set in pairs, moving diagonally down from the side of the head toward the nose and chin. The man facing me had seven such scars worked ceremonially worked into the tissue of his countenance, the highest being red, the next yellow, the next blue, the fourth black, then two yellow, then black again. The faces of the men I saw were all scarred differently, but each was scarred. The effect of the scars, ugly, startling, terrible, perhaps in part calculated to terrify enemies, had even prompted me, for a wild moment, to conjecture that what I faced on the Plains of Turia were not men, but perhaps aliens of some sort, brought to Gor long ago from remote worlds to serve some now discharged or forgotten purpose of Priest-Kings; but now I knew better; now I could see them as men; and now, more significantly, I recalled what I had heard whispered of once before, in a tavern in Ar, the terrible Scar Codes of the Wagon Peoples, for each of the hideous marks on the faces of these men had meaning, a significance that could be read by the Paravaci, the Kassars, the Kataii, the Tuchuks as clearly as you or I might read a sign in a window or a sentence in a book. At that time I could only read the top scar, the red, bright, fierce, cordlike scar that was the Courage Scar. It is always the highest scar on the face. Indeed, without that scar, no other scar can be granted. The Wagon Peoples value courage above all else.”—Nomads, 15-6

“I studied his heavy face, the fierce scarring that somehow ennobled it.”—Nomads, 26

“’When I have the time,” said Harold, ‘I will call one from the clan of Scarers and have the scar affixed. It will make me look even more handsome.’”

—Nomads, 274

Sharing Dirt and Grass: As we see from the quotes below, the bonds formed by the sharing of dirt and grass go beyond those dictated by culture—even on pains of death.

“Suddenly the Tuchuk bent to the soil and picked up a handful of dirt and grass, the land on which the bosk graze, and the land which is the land of the Tuchuks, and this dirt and grass he thrust in my hands and I held it.

“The warrior grinned and put his hands over mine so that our hands together held the dirt and grass, and were together clasped on it.

“’Yes,’ said the warrior, ‘Come in peace to the Land of the Wagon Peoples.’”—Nomads, 26

“’What fool is this!’ she demanded of Kamchak.

“’No fool,’ said Kamchak, ‘but Tarl Cabot, a warrior, one who has held in his hands with me grass and earth.’

“’He is a stranger,’ she said. ‘He should be slain!’

“Kamchak grinned up at her. ‘He has held with me grass and earth,’ he said.”—Nomads, 32

“’You would risk,’ I asked, ‘The herds—the wagons—the peoples?’

Both Kamchak and I knew that the Priest-Kings were not lightly to be disobeyed. Their vengeance could extend to the total and complete annihilation of cities. Indeed their power, as I knew, was sufficient to destroy planets.

“’Yes,’ said Kamchak.

“’Why?’ I asked.

“He looked at me and smiled. ’Because,’ said he, ‘we have held together grass and earth.’”—Nomads, 52

Slave Punishment among the Wagon Peoples:

“I had been afraid, from time to time, that they might, losing patience with what must seem to them to be the most utter nonsense, order her beaten or impaled.”—Nomads, 46

“Once, it might be noted, she returned from searching for fuel with the dung sack, dragging behind her, only half full. ‘It is all I could find,’ she told Kamchak. He then, without ceremony, thrust her head first in the sack and tied it shut. He released her the next morning. Elizabeth Cardwell never again brought a half-filled dung sack to the wagon of Kamchak of the Tuchuks.”—Nomads, 65.

"‘I have a knife!’ cried Aphris in fury.

“...When Kamchak had drunk the cup of wine he looked again at Aphris.' For what you have done,' he said, 'it is common to call one of the Clan of Torturers.' "-Nomads, 142

“By this time Elizabeth had returned with the whip and bracelets, and had handed them to Kamchak. She then went to stand by the left, rear wheel of the wagon. There Kamchak braceleted her wrists high over her head about the rim and one of the spokes. She faced the wheel…

"'There is no escape from the wagons,' he said.

"Her head was high. 'I know,' she said.

"'You lied to me,' he said, 'saying you went to fetch water.'

"'I was afraid,' said Elizabeth.

"'Do you know who fears to tell the truth?' he asked.

"'No,' she said.

"'A slave,' said Kamchak.

“He ripped the larl’s pelt from her and I gathered she would wear it no longer.

“She stood well, her eyes closed, her right cheek pressed against the leather rim of the wheel. Tears burst from between the tightly pressed lids of her eyes but she was superb, restraining her cries.”—Nomads, 168

"'No!' cried Elizabeth Cardwell. 'No!' But Kamchak was pulling her by the bracelets toward an empty sleen cage mounted on a low cart near the wagon, into which, still braceleted, he trust her, then closing the door, locking it.

"She could not stand in the low, narrow cage, and knelt, wrists braceleted, hands on the bars...

"...Kamchak, for a Tuchuk, was not unkind. The punishment for a runaway slave is often grevious, sometimes culminating in death...Elizabeth, in her way, was fortunate. As Kamchak might have said, he was permitting her to live. I did not think she would be tempted to run away again.

"I saw Aphris sneaking to the cage to bring Elizabeth a dipper of water. Aprhis was crying."-Nomads, 169

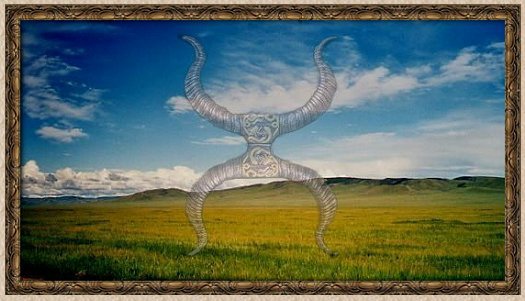

Standards and Brands of the Four Wagon Peoples:

"I observed the special wagon, drawn by a dozen bosk, being pulled up the hill, into which the standard, when uprooted, would be set. In a few minutes the great pole of the standard had been mounted on the wagon and was descending the hill..."--Nomads, 233

"We moved slowly, walking the kaiila, in four long lines, the Tuchuks, the Kassars, the Kataii, the Paravaci...The standard bearer, holding aloft on a lance a representation of the four bosk horns, carved from wood, rode near us. At the head of our line, on a huge kaiila, rode Kutaituchik...

"Beside him, but as Ubars, rode three other men, whom I took to be chief among the Kassars, the Kataii, the Paravaci. I could see, surprisingly near the forefront of their respective lines, the other three men I had first seen on coming to the Wagon Peoples, Conrad of the Kassars, Hakimba of the Kataii and Tolnus of the Paravaci. These, like Kamchak, rode rather near their respective standard bearers. The standard of the Kassars is that of a scarlet, three-weighted bola which hangs from a lance; the symbolic representation of a bola, three circles joined at the center by lines, is used to mark their bosk and slaves...the standard of the Kataii is a yellow bow, bound across a black lance; their brand is also that of the bow, facing to the left; the Paravaci standard is a large banner of jewels beaded on golden wires, forming the head and horns of a bosk [--] its value is incalculable; the Paravaci brand is a symbolic representation of a bosk head, a semicircle resting on an inverted isoceles triangle.--Nomads, 106.

Turian Collars:

“She turned within the collar, as the Turian collar is designed to permit.”—Nomads, 161

“At last his fist was within the Turian collar itself, and he drew the girl, piteous and exhausted, to his lips.”—Nomads, 161

Turian Barter and Trade Relations:

“The Wagon Peoples, though enemies of Turia, needed and wanted her goods, in particular materials of metal and cloth, which are highly prized among the Wagons. Indeed, even the chains and collars of slave girls, worn often by captive Turian girls themselves, are of Turian origin. The Turians, on the other hand, take in trade for their goods—obtained by manufacture or trade with other cities—principally the horn and hide of the bosk, which naturally the Wagon Peoples, who live on the bosk, tend to have in plenty. The Turians also, I note, receive other goods from the Wagon Peoples, who tend to be fond of the raid, goods looted from caravans perhaps a thousand pasangs from the herds, indeed some of them even on the way to and from Turia itself. From these raids the Wagon Peoples obtain a miscellany of goods which they are willing to barter with the Turians, jewels, precious metals, spices, colored table salts, harnesses and saddles for the ponderous tharlarion, furs of small river animals, tools for the field, scholarly scrolls, inks and papers, root vegetables, dried fish, powdered medicines, ointments, perfumes and women, customarily plainer wenches they do not wish to keep for themselves; prettier wenches, to their dismay are usually kept with the wagons; some of the plainer women are sold for as little as a brass cup; a really beautiful girl, particularly of free birth and high caste, might bring as much as forty pieces of gold; such are, however, seldom sold; the Wagon Peoples enjoy being served by civilized slaves of great beauty and high station; during the day, in the heat and dust, such girls will care for the wagon bosk and gather fuel for the dung fires; at night they will please their masters. The Wagon Peoples sometimes are also willing to barter silks to the Turians, but commonly they keep these for their own slave girls, who wear them in the secrecy of the wagons…It might be added that there are two items which the Wagon Peoples will not sell or trade to Turia, one is a living bosk and the other is a girl of that city itself…”—Nomads, 57-8

“This afternoon Kamchak and I, leading four pack kaiila, had entered the first gate of nine-gated Turia."On the pack animals were strapped boxes of precious plate, gems, silver vessels, tangles of jewelry, mirrors, rings, combs, and golden tarn disks, stamped with the signs of a dozen cities. These were brought as gifts to the Turians, largely as a rather insolent gesture on the part of the Wagon Peoples, indicating how little they cared for such things, that they would give them to Turians. Turian embassies to the Wagon Peoples, when they occurred, naturally strove to equal or surpass these gifts. Kamchak told me, a sort of secret I gather, that some of the things he carried have been exhanged back and forth a dozen times.”—Nomads, 86

“I found Turia to match my expectations. She was luxurious. Her shops were filled with rare, intriguing paraphernalia. I smelled perfumes that I had never smelled before.

“More than once we encountered a line of musicians dancing single file down the center of the street, playing on their flutes and drums, perhaps on their way to a feast.

“I was pleased to see again, though often done in silk, the splendid varieties of caste colors of the typical Gorean city, to hear once more the cries of peddlers that I knew so well, the cake sellers, the hawkers of vegetables, the wine vendor bending under a double verrskin of his vintage.

“We did not attract as much attention as I had thought we would, and I gathered that every spring, at least, visitors from the Wagon Peoples must come to the city. Many people scarcely glanced at us, in spite of the fact that we were theoretically blood foes. I suppose that life in high-walled Turia, for most of its citizens, went on from day to day in its usual patterns oblivious of the usually distant Wagon Peoples.”—Nomads, 87

“One disappointment to me in trekking through the streets of Turia was that a crier advanced before us, calling to the women of the city to conceal themselves, even the female slaves. Thus, unfortunately, save for an occasional furtive pair of dark eyes peering from behind a veil in a recessed casement, we saw in our journey from the gate of the city to the House of Saphrar none of the fabled, silken beauties of Turia.”—Nomads, 88

"'The Wagon Peoples need Turia,' said Kamchak, simply.

"I was thunderstruck. Yet it seemed to me true, for Turia was the main avenue of contact between the Wagon Peoples and the other cities of Gor, the gate through which trade-goods flowed into the wilderness of grasses that was the land of the riders of the kaiila and the herders of bosk. Without Turia, to be sure, the Wagon Peoples would undoubtedly be poorer.

"'And,' said Kamchak, 'the Wagon Peoples need an enemy...Without an enemy...they will never stand together--and if they fail to stand together, someday they will fall.'"--Nomads, 270

Taboos and Corresponding Punishments:

“The bosk is said to be the Mother of the Wagon Peoples, and they reverence it as such. The man who kills one foolishly is strangled in thongs or suffocated in the hide of the animal he slew; if, for any reason, the man should kill a bosk cow with unborn young he is staked out, alive, in the path of the herd, and the march of the Wagon Peoples takes its way over him.”—Nomads, 5

Tribal Colors of the Four Wagon Peoples: There are four distinct tribes of Wagon Peoples, each with its own signature color(s).

Tuchuks, the Wily People: Black with Red

"I could see he carried a small rounded shield, glossy, black, lacquered...”—Nomads, 10

“The kaiila of these men were as tawny as the brown grass of the prairie, save for that of the man who faced me, whose mount was a silken, sable black, as black as the lacquer of the shield.”—Nomads, 14

“Now the rider in front of me lifted the colored chains from his helmet, that I might see his face. It was a white face, but heavy, greased; the epicanthic folds of his eyes bespoke a mixed origin…

“Now the man facing me lifted his small, lacquered shield and his slender, black lance.

“’Hear my name,’ cried he, ‘I am Kamchak of the Tuchuks!’”—Nomads, 15, 16

“…And Kamchak, in the black leather of the Tuchuks…”—Nomads, 83

The Tuchuks also supplement their black attire with a good deal of red, as we see in the following quotes:

“…attached to her shoulders was a crimson cape; and her wild black hair was bound back by a strip of scarlet cloth.”—Nomads, 32

“Though he was stripped to the waist, there was about his shoulders a rich, ornamented robe of the red bosk, bordered with jewels; there hung a golden medallion, bearing the sign of the four bosk horns; he wore furred boots, wide leather trousers, and a red sash, in which was thrust a quiva.”—Nomads, 43

Kassars, the Blood People: Red

“The rider, too, wore a wind scarf. His shield was red. The Blood People, the Kassars.”—Nomads, 14

“’Tospit!’ called Conrad of the Kassars, the Blood People, and the girl hastened to set another fruit on the wand.

“There was a thunder of kaiila paws on the worn turf and Conrad, with his red lance, nipped the tospit neatly from the tip of the wand, the lance point barely passing into it, he having drawn back at the last instant.”—Nomads, 60

Kataii, the Black People: Yellow

“The second rider had halted there. He was dressed much as the first man, except that no chain depended from his helmet, but his wind scarf was wrapped about his face. His shield was lacquered yellow, and his bow was yellow. Over his shoulder, he, too, carried one of the slender lances. He was a black. Kataii, I said to myself.”—Nomads, 14

Paravaci, the Rich People: White with Black, Augmented with Jewels

The primary color of this tribe appears to be white; however, just as Tuchuks supplement their standard black with hints of red, the Paravaci offset their white fur with black leather. Of course, being the Rich Peoples, they also wear necklaces and belts of gold and dazzling gems!

“The fourth rider was dressed in a hood and cape of white fur. He wore a flopping cap of white fur which did not conceal the outlines of the steel beneath it. The leather of his jerkin was black. The buckles on his belt of gold…About the neck of the fourth rider there was a broad belt of jewels, as wide as my hand. I gathered this was ostentation. Actually I was later to learn that the jeweled belt is worn to incite envy and accrue enemies; its purpose is to encourage attack, that the owner might try the skill of his weapons, that he need not tire himself seeking for foes. I knew, though, from the belt, though I first misread its purpose, that the owner was Paravaci, the Rich Peoples, richest of the wagon dwellers.”—Nomads, 14

Ubar San and Omen Taking:

“It is near Turia, in the spring, that the Omen Year is completed, when the omens are taken usually over several days by hundreds of haruspexes, mostly readers of bosk blood and verr livers, to determine if they are favorable for a choosing of a Ubar San, a One Ubar, a Ubar who would be High Ubar, a Ubar of all the Wagons, a Ubar of all the Peoples, one who could lead them as one people.

“The omens, I understood, had not been favorable in more than a hundred years. I suspected that this might be due to the hostilities and bickerings of the peoples among themselves; where people did not wish to unite, where they relished their autonomy, where they nourished old grievances and sang the glories of vengeance raids, where they considered all others, even those of the other Peoples, as beneath themselves, there would not be likely to exist the conditions for serious confederation, a joining together of the wagons, as the saying is; under such conditions it was not surprising that the 'omens tended to be unfavorable'; indeed, what more inauspicious omens could there be? The haruspexes, the readers of bosk blood and verr livers, surely would not be unaware of these, let us say, larger, graver omens. It would not, of course, be to the benefit of Turia, or the farther cities, or indeed, any of the free cities of even northern Gor, if the isolated fierce peoples of the south were to join behind a single standard and turn their herds northward, away from their dry plains to the lusher reaches of the valleys of the eastern Cartius, perhaps even beyond them to those of the Vosk. Little would be safe if the Wagon Peoples should march.”—Nomads, 11-13

“It is in the spring that the omens are taken, regarding the possible election of the Ubar San, the One Ubar, who would be Ubar of all the Wagon, of all the Peoples.”—Nomads, 55

"...during the days of the Omen Taking. At that time Kutaituchik and other high men among the Tuchuks, doubtless including Kamchak, would be afield, on the rolling hills surrounding the Omen Valley, in which on the hundreds of smoking alters, the haruspexes of the four peoples would be practicing their obscure craft, taking the omens, trying to determine whether or not they were favorable for the election of a Ubar San..."-- Nomads, 146

"Coming over a low, rolling hill, we saw a number of tents pitched in a circle, surrounding a large grassy area. In the grassy area, perhaps about two hundred yards in diameter, there were literally hundreds of small, stone altars. There was a large circular stone platform in the center of the field. On the top of this platform was a huge, four-sided altar which was approached by steps on all four sides. On one side of this altar I saw the sign of the Tuchuks, and on the others, that of the Kassars, the Kataii and the Paravaci...

"There were a large number of tethered animals about the outer edges of the circle, and, beside them, stood many haruspexes. Indeed, I supposed there must be one haruspex at least for each of the many alters in the field. Among the animals I saw many verrs; some domestic tarsks, their tusks sheathed; cages of flapping vulos, some sleen, some kaiila, even some bosk; by the Paravaci haruspexes I saw manacled male slaves, if such were to be permitted; commonly, I understood from Kamchak, the Tuchuks, Kassars and Kataii rule out the sacrifice of slaves because their hearts and livers are thought to be, fortunately for the slaves, untrustworthy in registering portents; after all, as Kamchak pointed out, who would trust a Turian slave in the kes with a matter so important as the election of a Ubar San; it seemed to me good logic and, of course, I am sure the slaves, too, were taken with the cogency of the argument. The animals sacrificed, incidentally, are later used for food, so the Omen Taking, far from being a waste of animals, is actually a time of feasting and plenty for the Wagon Peoples, who regard the Omen Taking, provided it results that no Ubar San is to be chosen, as an occasion for gaity and festival...

"As yet the Omen Taking had not begun. The haruspexes had not rushed forward to the altars. On the other hand on each altar there burned a small bosk-dung fire into which, like a tiny piece of kindling, had been placed an incense stick.

"Kamchak and I dismounted and, from outside the circle, watched the four chief haruspexes of the Wagon Peoples approach the huge altar in the center of the field. Behind them another four haruspexes, one from each People, carried a large wooden cage, made of sticks lashed together, which contained perhaps a dozen white vulos, domesticated pigeons. This cage they placed on the altar. I then noticed that each of the four chief haruspexes carried, about his shoulder, a white linen sack, somewhat like a peasant's rep-cloth seed bag.

"'This is the first Omen,' said Kamchak, '--the Omen to see if the Omens are propitious to take the Omens.'

"'Oh,' I said.

"Each of the four haruspexes then, after intoning an involved entreaty of some sort to the sky, which at the time was shining beneficently, suddenly cast a handful of something--doubtless grain--to the pigeons in the stick cage.

"Even from where I stood I could see the pigeons pecking the grain in reassuring feeding frenzy.

"The four haruspexes turned then, each one facing his own minor haruspexes and anyone else who might be about, and called out, 'It is propitious!'...

"'This part of the Omen Taking always goes well,' I was informed by Kamchak.

"'Why is that?' I asked.

"'I don't know,' he said. Then he looked at me. 'Perhaps,' he proposed, 'it is because the vulos are not fed for three days prior to the taking of the Omens.'"--Nomads, 170-2

"I could now see the other haruspexes of the peoples pouring with their animals toward the altars. The Omen Taking as a whole lasts several days and consumes hundreds of animals. A tally is kept, day to day. One haruspex, as we left, I heard cry out that he had found a favorable liver. Another, from an adjoining altar had rushed to his side. They were engaged in a dispute. I gathered that reading the signs was a subtle business, calling for sophisticated interpretation and the utmost delicacy and judgement. Even as we made our way back to the kaiila I could hear two more haruspexes crying out that they had found livers that were clearly unfavorable. Clerks, with parchment scrolls, were circulating among the altars, presumably, I would guess, noting the names of haruspexes, their peoples, and their findings. The four chief haruspexes of the peoples remained at the huge altar, to which a white bosk was being slowly led."--Nomads, 172-3

General Info

. .

Men. .

Men. .

Women

. .

Women

. .

Slaves. .

Slaves. .

Visitors .

Visitors

|

|

|

|