Traditional Tuchuk Warfare & Defense

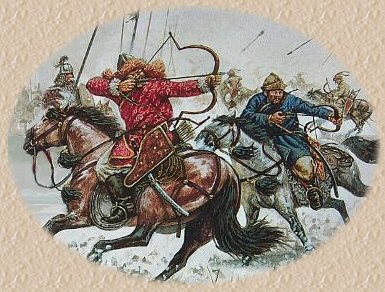

The kaiila, tem-wood lance, bola, horn bow, and saddle quiva are not the only unique aspects of Tuchuk warfare. The Wagon Peoples also employed an elaborate warning and communications system of bosk horn blasts, drum beats, and colored war lanterns which was capable of spanning hundreds of pasangs. Further, defense against an onslaught of Turians was clearly different from that against a raiding horde of Paravaci, Kassar, or Kataii. The following quotes from John Norman’s Nomads of Gor provide a wealth of information to aid us in our portrayal of authentic Tuchuk battle.

Basic Training

“It was said a youth of the Wagon Peoples was taught the bow, the quiva, and the lance before their parents would consent to give them a name, for names are precious among the Wagon Peoples, as among Goreans in general, and they are not to be wasted on one who is likely to die, one who cannot handle the weapons of the hunt and war. Until the youth has mastered the bow, the quiva, and the lance he is simply known as the first, or the second, and so on, son of such and such a father.”—Nomads, 11

Weapons and Protective Attire

An overview:

"And then I saw the first of the outriders, moving toward me, swiftly yet not seeming to hurry. I saw the slender line of his light lance against the sky, strapped across his back.

"I could see he carried a small rounded shield, glossy, black, lacquered; he wore a conical, fur rimmed iron helmet, a net of colored chains depending from the helmet protecting his face, leaving only holes for the eyes... I also noted, about his throat, now lowered, there was a soft leather wind scarf which might, when the helmet and veil was lifted, be drawn over the mouth and nose, against the wind and dust of his ride.

“He was very erect in the saddle. His lance remained on his back, but he carried in his right hand the small, powerful, horn bow of the Wagon Peoples and attached to his saddle was a lacquered, narrow, rectangular quiver containing as many as forty arrows. On the saddle there also hung, on one side, a coiled rope of braided bosk hide and, on the other, a long, three-weighted bola of the sort used in hunting tumits and men; in the saddle itself, on the right side, indicating the rider must be right handed, were the seven sheaths for the almost legendary quivas, the balanced saddle knives of the prairie. "—Nomads, 10-11

Bola and Bow: These long-range weapons enable a man to make a kill without coming any closer than is necessary. The horn bow is small and maneuverable, the bola a fearsome weapon with an almost inescapable sweep.

“Even had I slain two of them the others might have withdrawn and with their arrows or bolas brought me to the ground.”—Nomads, 18

“I saw him draw one of the quivas from a saddle sheath, loosen the long, triple-weighted bola from his side…

“Slowly, singing a guttural chant, a Tuchuk warrior song, he began to swing the bola. It consists of three long straps of leather, each about five feet long, each terminating in a leather sack which contains, sewn inside, a heavy, round, metal weight. It was probably developed for hunting the tumit, a huge, flightless, carnivorous bird of the plains, but the Wagon Peoples use it also, and well, as a weapon of war. Thrown low the long straps, with their approximate ten-foot sweep, almost impossible to evade, strike the victim and the weighted balls, as soon as resistance is met, whip about the victim, tangling and tightening the straps. Sometimes legs are broken. It is often difficult to release the straps, so snarled do they become. Thrown high the Gorean bola can lock a man’s arms to his sides; thrown to the throat it can strangle him; thrown to the head, a difficult cast, the whipping weights can crush a skull. One entangles the victim with the bola, leaps from one’s mount, and with the quiva cuts his throat…

“The Tuchuk handled it well. The three weights at the end of the straps were now almost blurring in the air and he, his song ended, the reins in his left hand, quiva blade clenched between his teeth, bola in his swinging, uplifted right arm, suddenly cried out and kicked the kaiila into its charge…

“It would be safest to throw low. It would be a finer cast, however, to try for the throat or head…

“To the head came the flashing bola moving in its hideous, swift revolution almost invisible in the air and I, instead of lowering my head or throwing myself to the ground, met instead the flying weighted leather with the blade of the Koroban short sword…”—Nomads, 24-5

“The bow of course, small, for use from the saddle, lacks the range and power of the Gorean longbow or crossbow; still, at close range, with considerable force, flying rapidly, arrow after arrow, it is a fearsome weapon.”—Nomads, 66-7

The Lance: Light and flexible, the delicate lance is more like a saber or rapier than the jousting tool of Medieval Europe.

“His lance had a rider hook under the point, with which he might dismount opponents.”—Nomads, 14

“As one, the lances were lowered. The lances of the Wagon Peoples are not couched. They are carried in the right fist, easily, and are flexible and light, used for thrusting, not the battering-ram effect of the heavy lances of Europe’s High Middle Ages. Needless to say, they can be almost as swift and delicate in their address as a saber. The lances are black, cut from the poles of young tem trees. They may be bent almost double, like finely tempered steel, before they break. A loose loop of boskhide, wound twice around the right fist, helps to retain the weapon in hand-to-hand combat. It is seldom thrown.”—Nomads, 15

“One, the Tuchuk, I might have slain with a cast of the heavy Gorean war spear; the others would have had free play with their lances. I might have thrown myself to the ground as the larl hunters from Ar, once their weapon is cast, covering myself with the shield; but then I would have been beneath the paws of the four squealing, snorting kaiila, while the riders jabbed at me with lances, off my feet, helpless.”—Nomads, 17

“The Tuchuk warrior lifted his lance in triumph, in the same instant slipping his fist into the retention knot and kicking the roweled heels of his boots into the silken flanks of his mount, the animal springing towards me and the rider in the same movement, as if one with the beast, leaning down from the saddle, lance slightly lowered, charging.

“The slender, flexible wand of the lance tore at the seven-layered Gorean shied, striking a spark from the brass rim binding it, as the man had lunged at my head.”—Nomads, 23

The Quiva: This long, balanced saddle knife is used less for close combat and more for swift, expert throwing. A sheath of seven of these knives is hung on the front of a warrior’s saddle, to the right of the pommel if he is right-handed, to the left if he is a southpaw. As with the bow, the bola, and the lance, the saddle quiva allows a Tuchuk to kill without making himself an easy-to-reach target. From the quote below, one may gather that the quiva is used at close range only when its wielder is assured of an easy slice to the throat of his opponent.

“I saw him draw one of the quivas from a saddle sheath, loosen the long, triple-weighted bola from his side…

“One entangles the victim with the bola, leaps from one’s mount, and with the quiva cuts his throat.

“Quiva blade now clenched between his teeth, bola in his swinging, uplifted right arm…

“…the Tuchuk leaped from the kaiila, quiva in hand, to find himself unexpectedly facing a braced warrior of Koroba, sword drawn.

“The quiva reversed itself in his hand, an action so swift I was only aware of it as his arm flew back, his hand on the blade, to hurl the weapon.

“It sped toward me with incredible velocity over the handful of feet that separated us. It could not be evaded, but only countered, and countered it was by the Koroban steel in my hand, a sudden ringing, sliding flash of steel and the knife was deflected from my breast.”—Nomads, 24-5

“I was most fond, perhaps, of the balanced saddle knife, the quiva; it is about a foot in length, double edged; it tapers to a daggerlike point…At forty feet I could stroke a thrown tospit; at one hundred feet I could strike a layered boskhide disk, about four inches in width, fixed to a lance thrust in the turf.”—Nomads, 67

The Kaiila: A fearsome beast, the kaiila is an extension of the rider, providing extra weapons with its teeth and claws, dodging and drawing false casts of the spear of its own accord, and providing an awesome trampling force with its great height and weight. One would do well to keep one’s kaiila a spear’s length from a standing, sword-wielding warrior, however; a well-placed swing would take the legs from your mount.

“The charge of the Tuchuk, in spite of its rapidity and momentum, carried him no more than four paces beyond me. It seemed scarcely had he passed than the kaiila had wheeled and charged again, this time given free rein, that it might tear at me with its fangs.

“I thrust with the spear, trying to force back the snapping jaws of the screaming animal. The kaiila struck, and then withdrew, and struck again. All the time the Tuchuk thrust at me with his lance. ..Then the animal seized my shield in its teeth and reared lifting it and myself, by the shield straps, from the ground.”—Nomads, 23

“Warily now the animal began to circle, in an almost human fashion, watching the spear. It shifted delicately, feinting, and then withdrawing, trying to draw the cast.

“I was later to learn that kaiila are trained to avoid the thrown spear. It is training which begins with blunt staves and progresses through headed weapons. Until the kaiila is suitably proficient in this art it is not allowed to breed. Those who cannot learn it die under the spear. Yet, at a close range, I had no doubt that I could slay the beast. As swift as may be the kaiila I had no doubt that I was swifter.”—Nomads, 24

“I might have thrown myself to the ground as the larl hunters from Ar, once their weapon is cast, covering myself with the shield; but then I would have been beneath the paws of the four squealing, snorting kaiila, while the riders jabbed at me with lances, off my feet, helpless.”—Nomads, 17

“He did not buy the kaiila near the wagon of Yachi of the Leather Workers though apparently it was a splendid beast. At one point, he wrapped a heavy fur and a leather robe about his left arm and struck the beast suddenly on the snout with his right hand. It had not struck back at him swiftly enough to please him, and there were only four needlelike scratches in the arm guard before Kamchak had managed to leap back and the kaiila, lunging at its chain, was snapping at him. ‘Such a slow beast,’ remarked Kamchak, ‘might in battle cost a man his life.’ I supposed it was true. The kaiila and its master fight in battle as one unit, seemingly a single savage animal, armed with teeth and lance.”—Nomads, 170

Communication Systems

Bosk Horn Signals and Defending Against Other Tribes of Wagon Peoples: Bosk horns are used to signal charges and retreats as well as to direct formations. Rather than using such signals to move the wagons to safety, as when city raiders on tarnback threaten the Wagon Peoples, the wagons—and even the bosk—are used in defense when another tribe comes raiding.

“I did not wish to remain on the crest of this hill long enough to allow the left and right flanks of the Paravaci—rapidly assembling—to fold about my men and so, in less than four Ehn—as their astonished, disorganized center fell back—our bosk horn sounded our retreat and our men, as one, withdrew to the herds—only a moment before the left and right flanks of the Paravaci would have closed upon us. We left them facing one another, cursing, while we moved back through our bosk, keeping them as a shield.”—Nomads, 259

“Once again our bosk horns sounded and this time my Thousand began to cry out and jab the animals with their lances, turning them toward the Paravaci. Thousands of animals were already turned toward the approaching enemy and beginning to walk when the Paravaci realized what was happening. Now the bosk began to move more swiftly, bellowing and snorting. And then, as the Paravaci bosk horns sounded frantically, our bosk began to run, their mighty heads with the fearsome horns nodding up and down, and the earth began to tremble and my men cried out more and jabbed animals, riding with the flood and the Paravaci with cries of horror that coursed the length of their entire line tried to stop and turn their kaiila but the ranks behind them pressed on and they were milling there before us, confused, trying to make sense out of the wild signals of their own bosk horns when the herd, horns down, now running full speed, struck them.

“It was the vengeance of the bosk and the frightened, maddened animals thundered into the Paravaci lines goring and trampling both kaiila and rider…”—Nomads, 260

“The battle was joined at the seventh Gorean hour and, as planned, as soon as the Paravaci center was committed, the bulk of our forces wheeled and retreated among the wagons, the rest of our forces then turning and pushing through the wagons together. As soon as our men were through the barricade they leaped from their kaiila, bow and quiver in hand, and took up prearranged positions under the wagons, between them, or on them, and behind the wagon box planking, taking advantage of the arrow ports therein.

“The brunt of the Paravaci charge almost tipped and broke through the wagons, but we had lashed them together and they held. It was like a flood of kaiila and riders, weapons flourishing, that broke and piled against the wagons, the rear flanks pressing forward on those before them. Some of the rear flanks actually climbed fallen and struggling comrades and leaped over the wagons to the other side, where they were cut down by archers and dragged from their kaiila to be flung under the knives of free Tuchuk women.

“At a distance of little more than a dozen feet thousands of arrows were poured into the trapped Paravaci and the yet they pressed forward, on and over their brethren, and then arrows spent, we met them on the wagons themselves with lances in our hands, thrusting them back and down.”—Nomads, 261-262

Signal Drums and Other Uses of Bosk Horns: Drums and bosk horns can be used for other reasons, as well...

”Then we heard the pounding of a small drum and two blasts on the horn of a bosk.

”Kamchak read the message of the drum and horn.

”’A prisoner has been brought to camp,’ he said.”—Nomads, 33

War Lanterns: Perhaps the most interesting of all communication systems employed in the immense camps of the Wagon Peoples is the colored war lantern.

“War lanterns, green and blue and yellow, were already burning on poles in the darkness, signaling the rallying grounds of the Orlus, the Hundreds, and the Oralus, the Thousands. Each warrior of the Wagon Peoples, and that means each able-bodied man, is a member of an Or, or a Ten; each ten is a member of an Orlu, or Hundred; each Orlu is a member of an Oralu, a Thousand. Those who are unfamiliar with the Wagon Peoples, or who know them only from the swift raid, sometimes think them devoid of organization, sometimes conceive of them as mad hordes or aggregates of wild warriors, but such is not the case. Each man knows his position in the Ten, and the position of his Ten in the Hundred, and of the Hundred in the Thousand. During the day the rapid movements of these individually maneuverable units are dictated by bosk horn and movements of the standards; at night by the bosk horns and the war lanterns slung on high poles carried by riders.” —Nomads, 175

“Then the women climb to the top of the high sides on the wagons and watch the war lanterns in the distance, reading them as well as the men. Seeing if the wagons must move, and in what direction.”—Nomads, 176

Formations and Organization:

“I could now see as well, though separated by hundreds of yards, three other riders approaching. One was circling to approach from the rear.”—Nomads, 13

“Those who are unfamiliar with the Wagon Peoples, or who know them only from the swift raid, sometimes think them devoid of organization, sometimes conceive of them as mad hordes or aggregates of wild warriors, but such is not the case. Each man knows his position in the Ten, and the position of his Ten in the Hundred, and of the Hundred in the Thousand.”—Nomads, 175

“Rank by rank the warriors on the kaiila, dour, angry, silent, turned their mounts away from the city and slowly went to find the wagons, save for the Hundreds that would flank the withdrawal and form its rear guard.”—Nomads, 233

“I then looked once more over the parapet. The dust was closer now. In a moment I would be able to see the kaiila, the flash of light from the lance blades. Judging from the dust, its dimensions, its speed of approach, the riders, perhaps hundreds of them, the first wave, were riding in a narrow column, at full gallop. The narrow column, and probably the Tuchuk spacing, a Hundred and then the space for a Hundred, open, and then another Hundred, and so on, tends to narrow the front of dust, and the spaces between Hundreds gives time for some of the dust to dissipate and also, incidentally, to rise sufficiently so that the progress of the consequent Hundreds is in no way impeded or handicapped. I could now see the first Hundred, five abreast, and then the open space between them, and then the second Hundred. They were approaching with great rapidity. I now saw a sudden flash of light as the sun took the tips of Tuchuk lances.”—Nomads, 243

“Raising my arm and shouting, I led the Thousand toward [the Paravaci], hoping to catch them before they could form and charge. Our bosk horns rang out and my brave Thousand, worn in the saddle, weary, on spent kaiila, without a murmur or a protest, turned and following my lead struck into the center of the Paravaci forces.

“In an instant we were embroiled among angry men—the half-formed, disorganized Hundreds of the Paravaci—striking to the left and right, shouting the war cry of the Tuchuks. I did not wish to remain on the crest of this hill long enough to allow the left and right flanks of the Paravaci—rapidly assembling—to fold about my men and so, in less than four Ehn—as their astonished, disorganized center fell back—our bosk horn sounded our retreat and our men, as one, withdrew to the herds—only a moment before the left and right flanks of the Paravaci would have closed upon us. We left them facing one another, cursing, while we moved back through our bosk, keeping them as a shield.”—Nomads, 259

Roles of Women, Children, and Slaves

”When the bosk horns sound the women cover the fires and prepare the men’s weapons, bringing forth arrows and bows, and lances. The quivas are always in the saddle sheaths. The bosk are hitched up and the slaves, who might otherwise take advantage of the tumult, are chained.

“Then the women climb to the top of the high sides on the wagons and watch the war lanterns in the distance, reading them as well as the men. Seeing if the wagons must move, and in what direction.

”I heard a child screaming its disgust at being thrown in the wagon.”—Nomads, 175-176

“Some of the rear flanks actually climbed fallen and struggling comrades and leaped over the wagons to the other side, where they were cut down by archers and dragged from their kaiila to be flung under the knives of free Tuchuk women.”—Nomads, 262

And, when raiding another tribe of the Wagon People, the enemy’s women also have their uses:

“Shortly after dawn we discovered the Paravaci forming in their Thousand away from the herd, repairing to strike the wagons from the north, slaying all living things they might encounter, save women, slave or free. The latter would be driven in front of the warriors through the wagons, both slave girls and free women stripped and bound together in groups, providing shields against arrows and lance charges on kaiilaback for the men advancing behind them.”—Nomads, 261

Slaves do help out with the readying of the wagons prior to being chained—and men as well, if need be—as we see in this quote:

“In short time, Kamchak and I had reached our wagon. Aphris had had the good sense to hitch up the bosk. Kamchak kicked out the fire at the side of the wagon...” Nomads, 176

Further, slaves were usually but not always chained in the event of warfare. As we see in this quote, sometimes slaves were instead caged:

”Kamchak unlocked the [sleen] cage and thrust Aphris inside with Elizabeth. She was slave and would be secured, that she might not seize up a weapon or try to fight or burn wagons...It was better, I knew, for her to be secured as she was rather than chained in the wagon, or even to the wheel. The wagons, in Turian raids, are burned.”—Nomads, 176

Thus, we see the basic difference between a raid from another tribe of the Wagon Peoples as opposed to one from those of the cities: whereas other tribes would swarm in and drag off whatever booty they could, those of the cities would seek only to destroy. This makes clear the need to douse camp fires lest their flickering light make an easy target of a wagon.

See also: Weapons Training

General Info

. .

Men. .

Men. .

Women

. .

Women

. .

Slaves. .

Slaves. .

Visitors .

Visitors

|

|

|

|